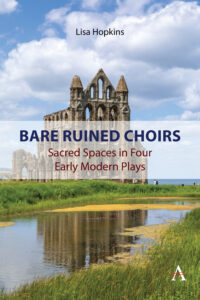

This is a guest post by Lisa Hopkins, author of Bare Ruined Choirs: Sacred Spaces in Four Early Modern Plays

When Shakespeare writes in Sonnet 73 of ‘Bare ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang’, he was referring to the Dissolution of the Monasteries, begun in 1536 by King Henry VIII as part of his attempt to break away from the power of the Pope, who had refused to allow him to divorce his first wife Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn. Henry had married Anne anyway in early 1533, and by the time the first, smaller monasteries were closed in 1536, he had already tired of her after her failure to bear him a son; she was executed on 19 May 1536 on a trumped-up charge of adultery, but the king went ahead with the suppression of all religious houses in England and Wales because there were such rich pickings to be had. Land owned by the monasteries could be reassigned to loyal followers; lead from their roofs could be pillaged and brasses on tombs could be looted and melted down; and their enormous wealth could enrich the coffers of the king himself. There was nothing for Henry not to like.

Not everyone was so pleased. The worst sufferers were the dispossessed monks and nuns themselves; turfed out of their homes and stripped of their vocations, they had to cope as best they could in secular society (and were unable to marry because of the vows they had taken). Poor people who had depended on the monasteries for food handouts and other forms of charity were also bereft, while the rich might find the tombs of their ancestors suddenly exposed underneath bare sky or sheltered only by ruins. Many of those ruins now form attractive and much-visited features of the landscape, but in their day, they testified to loss, desecration and trauma.

This book explores how that trauma makes itself felt in four plays written in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Two, Thorney Abbey and A Knack to Know a Knave, are anonymous; A Shoemaker a Gentleman is by William Rowley, known for his collaborations on a couple of other plays; and the fourth, The Lovesick King, is by Anthony Brewer, of whom we know nothing at all. They are set variously in Thorney Abbey, the original foundation which later became Westminster Abbey; the northern English town of Hexham, where the abbey resisted Henry and the canons were executed; the important North Welsh pilgrimage site of St Winifred’s Well and the English shrine of St Albans; and the Anglo-Saxon royal necropolis at Winchester and a famous church in Newcastle. None of these plays is anywhere near as famous as Shakespeare’s, but they share concerns with Hamlet, Macbeth and King Lear and also with Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. The book aims to shed light on these better-known plays as well as introducing some new ones and showing how they comment on this enormous change to the fabric of life in early modern England and Wales.